Written by

Nikita Dumitruc

Published on

19 Jan 2026

Copy link

Financial Pressure Has Redefined the Student Experience

Just as universities have faced sustained financial pressures in recent years, students have experienced similar challenges. The recent data in the SAES and NatWest reports indicate that financial strain is now a defining feature of the average student experience, shaping how students allocate time, energy, and attention across study, work, and wider life commitments.

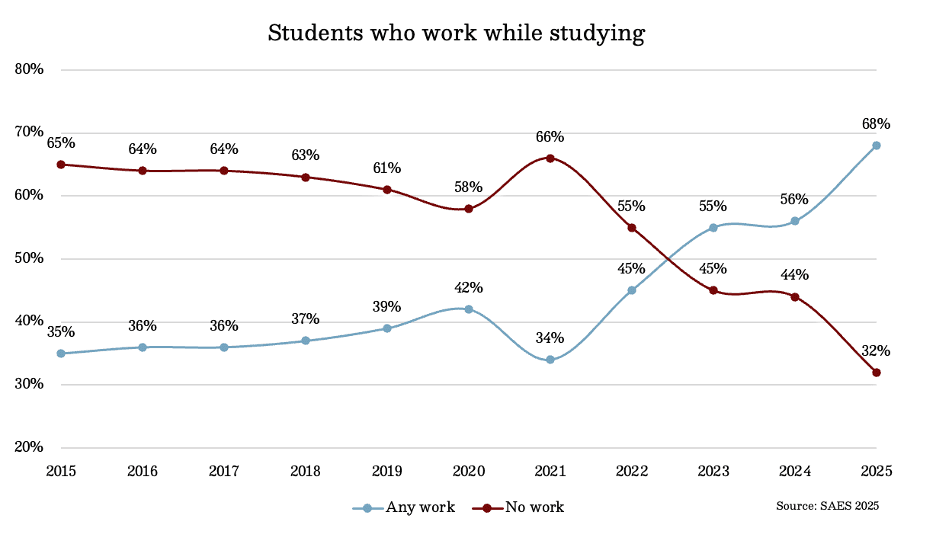

In 2015, only 35% of students undertook part-time work during term time. A decade later, this pattern has reversed: 68% of students now work alongside their studies, while just 32% do not. The average student spends 8.9 hours per week in paid employment. Viewed by itself, this figure is not inherently negative and may even be interpreted as a positive signal of employability and skills development. However, this number masks a more significant structural shift in how students finance their education and manage competing demands on their time.

Term-Time Work and the Fragmentation of Student Time

The NatWest Student Living Index 2025, based on a survey of over 5,000 UK undergraduates, shows that term-time work is now one of the three largest sources of student income, alongside parental support and student loans. At the same time, average rents have continued to rise, with students paying an average of £562 per month nationally (substantially more in London) while 47% report running out of money before the end of term. These pressures are not marginal: 31% of students report reducing meals, and 25% report cutting back on heating to manage costs, highlighting the severity of financial constraint.

Hours per week in paid work | 2022 | 2025 | 3Y % change |

0 | 55% | 32% | -41.82% |

1-5 | 11% | 16% | 45.45% |

6-10 | 13% | 18% | 38.46% |

11-15 | 8% | 12% | 50% |

16-20 | 8% | 12% | 50% |

20+ | 5% | 10% | 100% |

Against this backdrop, more students are being pushed into paid work for longer hours. While the average working student now undertakes 13.1 hours of employment per week, a level that may be manageable if carefully balanced, the distribution of working hours reveals a more concerning trend. Between 2022 and 2025, the proportion of students working more than 20 hours per week doubled from 5% to 10%, while the share of students not working at all fell sharply. Growth occurred across every working-hours band, indicating not only that more students are working, but that a growing minority are committing substantial time to employment.

The “Full-Time” Study Assumption

This matters because time is a finite resource. QAA guidance suggests that each academic credit equates to approximately 10 hours of learning, implying that full-time students are supposed to dedicate a significant portion of their time to independent study alongside contact hours. In practice, however, the learning time available per credit is highly uneven. Students working 16–20 hours or more each week must compress their academic work into increasingly narrow time windows, often late evenings or weekends.

Evidence from the NatWest Student Living Index 2025 reinforces this concern. The data shows that academic study time has continued to decline since the pandemic, while time spent socialising, pursuing hobbies, and engaging in entertainment has rebounded to above pre-pandemic levels. Students are not disengaging from university life; they are adapting to a new norm in which paid work, study, and social life are tightly interwoven.

Time Scarcity as a Structural Risk to Quality and Equity

The central issue is not students' behaviour, but that universities persist in structuring full-time degrees for a reality that is changing. "Full-time study" is embedded in policy, yet no longer matches most students' lived experience.

The present-day undergraduate timetable is fragmented by necessity. Paid employment, long commuting, financial stress, caring responsibilities, and irregular availability are no longer edge cases. For a growing proportion of students, they are the norm.

Yet curriculum design continues to assume large, uninterrupted blocks of discretionary study time. Support models presume that students can attend fixed office hours, plan ahead, and quickly recover from missed lectures, seminars, or readings. Assessment structures assume linear engagement and predictable study rhythms. These assumptions are increasingly misaligned with reality.

This mismatch is more than a wellbeing concern; it poses a structural threat to learning quality, equity, and outcomes. As time scarcity becomes the norm, academic success increasingly depends on students' flexibility, not ability. Upholding outdated "full-time" standards erodes, rather than preserves, academic standards.

Academic Support as Infrastructure

Universities, therefore, face a strategic choice. They can continue to interpret declining engagement as an individual student deficit. Or they can acknowledge that the underlying operating model of full-time education is changing and is no longer fit for the purpose it once served.

If learning time is fragmented, academic support cannot remain optional, reactive, or bounded by staff availability. It must become continuous, adaptive, and embedded directly into the learning environment. Support must meet students where learning actually happens: in short windows, at irregular hours, and at the point of confusion. Rather than days later in a scheduled meeting, lecture, or email exchange.

In this context, tools like Plato should not be understood as productivity aids for busy students or as AI substitutes for teaching. They represent something more fundamental: an effort to realign institutional learning support with the realities of current and future learners. By embedding module-specific academic support directly into the VLE, and by surfacing real-time insight into where students are struggling, such systems treat time scarcity as a design constraint rather than a personal failure.

The data is clear: a growing proportion of students no longer study full-time in the traditional sense. The critical question is whether universities will acknowledge and adapt to this new reality or continue to optimise for a model that is rapidly disappearing and, in doing so, becoming even more disengaged from students as the result.